Breaking Through the Barrier

Norwalk English language learners share the benefits and barriers of learning a new language

May 1, 2023

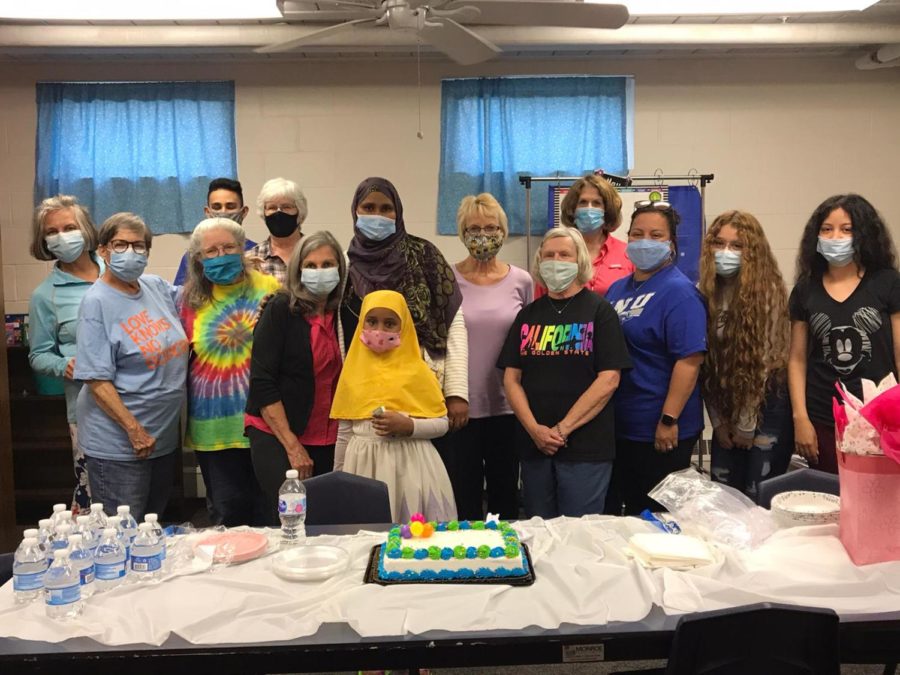

Norwalk is home to a number of non-native English speakers who have found a sense of community within an English-teaching program housed at Norwalk Christian Church.

Currently consisting of 12 students and 19 volunteers, this program teaches students of various ages around the Norwalk area how to read, write, speak, and comprehend English.

Volunteer Doris Cose said this class has led many students to achieve great goals using their English education.

“Two of our students have gained their citizenship, we’ve had two that have gotten their driver’s license, and they’ve gotten jobs,” she said. “We love them all. They all just have to remember when they’re learning English, they know two languages. That’s amazing.”

One student, Zahara, took the U.S. citizenship test where she had to learn the answers to 100 different questions before being asked to verbalize 12 more. She thanked her teachers for helping her achieve this goal.

“When I first started class, I didn’t know English,” she said. “No reading, no spelling, and the teacher helps me. It’s really nice.”

Working with English

Some have found this class helps to utilize their English skills in a work setting. Brenda is another student who is entering a vendor fair this April, selling a number of things such as balloons, gift baskets, tablecloths, centerpieces, and more designed for special events and celebrations. Brenda said that English will help her to communicate with her customers.

“I speak in Spanish at home,” she said. “My husband does more practice with my son in English, but for me it is difficult. I have a goal to learn English more this year for my job.”

Another student, Liz, said she faces some difficulty regarding her first language at her medicine school.

“We are going to a medicine college, and I want to study public health,” she said. “They tell me my first language is Spanish, and you have to prove to them you speak English way better.”

Liz said she also works at an elementary school, where she has gained the ability to communicate in English. However, she said her college still discriminates against her first language.

“I told them I’m working at the elementary school, and I understand English,” she said. “In Texas, they don’t discriminate my language, they respect my language. But here, I don’t know.”

Cose said schools in Iowa would benefit from having a Spanish speaker like Liz.

“But do you know how lucky they would be to have someone who speaks Spanish?,” she said.

Liz’s husband, Jose, said he has noticed a pattern regarding discrimination of first languages at schools or universities.

“Something I’ve noticed, especially at universities or college, is if you say your first language is not English, sometimes they can discriminate you,” he said. “They may require you to have certain certificates to prove, but I didn’t have that experience honestly.”

Jose said when he first began his job, he had hesitations with communication.

“I work, and at the beginning I was a little bit afraid,” he said. “For me, it requires all the time to communicate, and most of the people are from different states. So, I was a little bit afraid if I wasn’t communicating really well with them, but over time I got used to it and went with the flow.”

Language in Education

Many parents of the group have shared that it can be harder for them to learn English than their children, due to these children attending hours of school every day in English. Zahara said her son has reduced his use of Somali in half due to school.

“In kindergarten and preschool, he used a lot of Somali,” she said. When Zahara asked why he is losing his Somali, she said he told her, “‘Mama, there is eight hours of school, with a teacher and English, you’re home a little bit, then you wake up and school again.’”

Zahara’s daughter, Farhiya, is also a student at Norwalk. When asked if English concepts are harder to grasp, Farhiya gave multiple examples.

“In Somali words are pronounced how they are spelled, but in English it’s like the opposite,” she said. “The same word being pronounced the same but being spelled differently, I don’t like that at all. Or random letters and words being silent.”

Erika is a college student at DMACC. She said that everyone in college speaks English, as she only has one professor who speaks Spanish.

“I don’t understand some things because there are some new words for me,” she said. “When people are using body language, it’s easier for me to understand. In this class I feel comfortable talking in English, but I don’t feel that at school.”

While students at the high school are required to take a second-language class, they are not required to use that language in their everyday lives outside of the Spanish or French classroom. However, for these ELL students, they are required to learn and utilize the language at the same time.

Erika’s sister, Paola, is another student at Norwalk who said it can be difficult to speak English at school.

“It’s harder because my first language is Spanish, and I have to speak English at the school with people who don’t speak Spanish,” she said. “When you are learning English at first, you can understand everything other people are saying. But when it is your turn to talk, it is just difficult.”

This program is one way students like Erika and Paola can learn English in a safe environment. Paola said she cannot find this same level of comfort at the school.

“If we say a word that they (the teachers) don’t understand, they try to help us and try to think of what it is,” she said. “But if we say that at the school, (the students) are like ‘Oh, you’re Mexican, right?’ If you speak in Spanish at the school, they’ll say racist things. So, that’s how it feels when you go to a school where they only speak English and no other language.”

Paola said she does not have opportunities to speak Spanish beyond Spanish class because of how her peers will react.

“When the students are from here, they’re like ‘oh my gosh you have an accent,’ and that makes you feel like, that’s why we don’t speak,” she said. “In Spanish class obviously you have to speak in Spanish, but that’s it. That’s why we feel comfortable talking here, because they don’t judge us.”

Paola said the Norwalk ELL program does a good job of making the students feel comfortable and heard while learning.

“I will say that this class is like a safe place for you because they don’t judge you, they try to help you in every way that they can,” she said. “They can be our teachers, but they can be our friends too. We can talk about things that are outside of school, or things that are hard for us, and they try to help us all the time.”

Beyond the Classroom

The struggles these students face go beyond a work or school setting. One student, Delia, shared her first time being greeted in English.

“The first time when I heard someone say ‘Hi,’ I thought she must have a hurt belly or something,” she said. “In my mind, because I don’t understand it in English, I think ‘Oh, maybe she has pain in her belly.’”

Many recalled feeling the same way in public, such as in a grocery store. One said when she first went to the store, she wasn’t sure how to ask for flour. Doris said certain words like this can be difficult in English when they have multiple meanings.

“Like a flower, but you can also make cookies or bread out of flour,” she said. “They’re said the same way, but when you spell it differently it means totally different things in English.”

Doris said the students are what motivate her to participate in the group.

“When I first started meeting students, that’s what did it for me,” she said. “I thought these people were amazing. We want them to know they are part of this community, too.”

Katie Routh, another volunteer, said this ELL program is already on its way to building community within Norwalk.

“One of the biggest goals, which was maybe an unintended goal that we didn’t realize was so important, was that we feel like family, we feel like a community now,” she said.